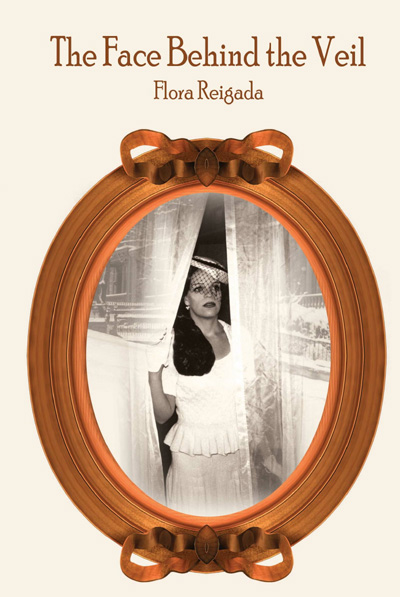

The Face Behind the Veil

by

Flora Reigada

by

Flora Reigada

Coipyright © Flora Reigada. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the author.

First published by AuthorHouse 05/11/04

ISBN: 1-4184-6404-X (e-book)ISBN: 1-4184-4364-6 (Paperback)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2004090565

Printed in the United States of America Bloomington, IN

This book is printed on acid free paper.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the author.

First published by AuthorHouse 05/11/04

ISBN: 1-4184-6404-X (e-book)ISBN: 1-4184-4364-6 (Paperback)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2004090565

Printed in the United States of America Bloomington, IN

This book is printed on acid free paper.

PART 1 – NAOMI'S STORY

CHAPTER 1

Labor pains sliced into Estelle’s abdomen as she awakened that March dawn in 1925. The buxom blonde's husband, Jacob, rushed into the cold mist to awaken her brother who lived nearby. The two men quickly returned. Franz, the only person the couple knew who owned a car, had agreed to drive Estelle to the hospital. Even in her pain, Estelle noticed the stench of the previous night’s bootleg whiskey on her brother’s breath. It added nausea to her discomfort. The pains stabbed deeper and harder as the young woman clutched Franz’s arm and waddled into the morning chill.

Glancing over her shoulder, Estelle managed a feeble wave to Jacob, who watched from the window. He remained behind to care for the couple’s two sleeping toddlers. A nervous Franz helped his swollen sister into the passenger seat of the Model T Ford. As it chugged along, each bump seemed to jostle the baby farther down the birth canal—making the woman feel as if she were being ripped apart.

Soon, the twenty-something blonde was at the hospital with her cries echoing down the corridors. At last, the gray haired, mustached doctor wrested the baby from her body. Estelle felt her flesh tearing as the newborn emerged.

“It’s a girl!” the doctor announced, lifting a membrane from the baby’s face.

The attending nurse stopped short, her eyes wide. “Why are you just tossing that aside? Don’t you know what it means? It's the rare birth veil—the sign of a prophet!”

“Nonsense,” the doctor chuckled, holding up the wailing infant for Estelle to see. “It’s just part of the amniotic sac.”

Despite her pain and blood loss, Estelle gazed at her daughter in awe. As a child, she overheard old women discussing “the veil.” One cackled that her father, a Navy captain during the War Between the States, had carried a veil aboard his ship.

“They’re supposed to bring good luck,” the stoop-shouldered woman said, clutching her cane. “Those born with the veil are gifted with second sight into the spiritual world.”

At the time, Estelle believed that. Now it was like a prophecy fulfilled in her own daughter. Indeed, this baby would see wonders and understand great mysteries.

Another girl, Estelle thought while drifting to sleep. Now I have two girls and a boy. I’ll name her Naomi. I read somewhere it means “my delight.” And I know that’s what this little one will always be.

Several days later, Estelle brought the dark-eyed infant home to the family’s cramped apartment on Staten Island, New York. In a row of brick apartment buildings, it ascended from the crest of a steep hill. The upper floors offered a panoramic view of New York Harbor and the hazy Manhattan skyline. From the bottom floor where Estelle, Jacob and their children lived, a few windows overlooked a tiny courtyard. With the building constructed into the hill, some of the family’s rooms were partially underground.

Just like being in a grave, Estelle would sometimes think. Stormy nights when cold winds howled up from the harbor, phantoms seemed to roam the darkness. Echoing foghorns sounded the agony of things seen and unseen.

And when he drank, Estelle’s husband, Jacob, seemed as haunted as the night. Although Estelle disliked his cigarette smoke that turned the apartment dusty and dingy, she hated the alcohol that turned his ebony eyes sad and distant. Even during Prohibition, he always managed to find illegal whiskey. But, so did most people Estelle knew.

Because Jacob was a faithful provider and a devoted family man, she accepted his drinking. It was part of the raven-haired man she adored, who provided her with the important “Mrs.” title. Estelle had been so thrilled to become Mrs. Kahn, she didn’t protest when her brother, Franz, tagged along on their honeymoon. After that, he and her new husband spent the week drinking.

Estelle wasn’t surprised or upset. Like other women of her time, she had learned her lessons well; Keep your mouth shut and never make any demands on a man. Otherwise, the consequences could prove disastrous. A nagging wife might drive a husband away. Aside from the disgrace, who would then provide for her? So for now, Estelle was content to care for her family and the occasional wounded bird she might find flapping on the sidewalk.

Oh well, she would sigh to herself. That’s men for you. Just like Mother always taught me, everything will be fine if you just leave them alone and be agreeable. I can’t complain. After all, Jake did land that great job as a projectionist at the theater.

Despite Jacob’s job, the young family never seemed to have enough money. Estelle hoped Jacob’s father would share some of his wealth.

Having left Germany because of a domineering father and anti-Semitism, Abraham Kahn was determined to never look back. Arriving in New York, the young man changed his name to Albert and his Jewish faith to Protestant. Albert’s conversion was not due to a change of convictions, however. He remained agnostic, attending church only for weddings and funerals.

After saving money from years of hauling sacks of coal, he purchased a group of row houses on Staten Island. Originally called Horton’s Row, the homes had gleaming hardwood floors, marble fireplaces and decorative columns. Leaving these intact, Albert converted the townhouses into apartments. He did the same with several weathered homes he purchased across the street.

The row houses included the building in which Estelle would live. More family members would move into other buildings. Estelle was grateful that her father-in-law let them all stay there for a nominal rent. Only two of Albert’s children moved out from under their father’s wing.

Thrifty with money, the elder Kahn amassed a small fortune. He and his wife, Rebekah, lived in the apartment above Estelle’s. Although Albert was fair-skinned with blond hair and blue eyes, his wife looked Eurasian, as did the couple’s children. No one could have guessed they were really cousins who had their marriage arranged by relatives in Germany. Using part of the money he had saved, Albert sent for his bride-to-be.

With silken black hair and onyx eyes, Estelle thought her mother-in-law had an exotic, oriental look. However, the hard work and adversity that showed on Rebekah's face, cast a shadow on her beauty.

Once home from the hospital, Estelle would walk the floors carrying little Naomi. Sometimes she would pause by the window, think of her mother-in-law and feel compassion. Of the thirteen children she bore, only six had survived.

It made Estelle wince to look at the older woman's discolored and bandaged legs. As she limped from chore to chore, a bulging vein would occasionally burst and bleed.

The memory made Estelle shudder. All that cooking, cleaning and scrubbing on a washboard. It’s no wonder the poor thing is in constant pain.

Like many others, Estelle suspected that Rebekah Kahn's pain went far deeper than her legs—it went straight to her heart. Rumors had long circulated among neighborhood housewives that Estelle’s father-in-law had a relationship with a woman family members called, “the slut on Victory Hill.”

Estelle agreed with other family members. If it did happen, she asked for it, the way she threw herself at him.

Estelle also thought it pained the older woman to have left her Jewish faith back in the old country. Only she and one daughter tried to preserve the traditions, such as occasionally lighting the menorah.

My father-in-law said we’d be better off leaving the past in Germany, Estelle recalled. That’s why he changed his name when he came here.

She wondered if some lines in her mother-in-law’s face had been etched by the unusual behavior of a son, Stanley. Only in his mid-twenties, he lived in the building with his sister, Rose. While eyeing him suspiciously, neighbors would whisper that he was strange. Seldom speaking, he was often seen wandering in remote and wooded areas of Staten Island.

Occasionally, he seemed to vanish into thin air, leaving the family searching for him days at a time. Neighbors would wince as they retold the gory tale of his only friend being found murdered.

“Red Quinn was his name. He was an old hobo. Some kids found his bloodied body in an alleyway five years ago and still have nightmares about it. They say they will never forget the way he looked, with frightened eyes wide open. The sight even shocked police, who found the broken whiskey bottle they say was used to kill poor Red.”

Although no arrests were ever made, neighbors suspected and feared Stanley.

And from nearby Tompkinsville Park, those neighbors watched his sister, Rose. Men watched her because she was beautiful. Women watched because they were jealous, not only of her beauty but also of her talent. She had the reputation of being a gifted seamstress in Manhattan's garment district. The jealousy fueled local gossip.

“Do you really think she’s seeing a married man?" they'd whisper.

Family members would defensively point out that he relentlessly pursued her but she rebuffed him.

Another sister, Eva, lived in one of the weathered houses with her husband, Ray and his two sons from a previous marriage. Neighbors often heard Ray yelling at Eva, and everyone knew he occasionally got a little carried away with his fists. No one thought much of it, though, not even Eva.

She often told family members, “Being married is better than being an old maid.”

Eva felt lucky to have caught the widower twelve years her senior. Unable to have children, she raised her husband's boys as though they were her own. The beatings and responsibilities of child rearing were a small price to pay for the security of having a husband.

Sisters-in-law and in their twenties, Eva and Estelle became good friends. Getting together to shop or take the children to the park, they’d occasionally visit the plump old Irish woman who told fortunes.

Birdie O’Brien lived nearby in another of the weathered houses, and read palms and tea leaves. Estelle’s fascination with the readings was the only thing that brought her to the gloomy apartment. Though it was kept tidy, something about the creaky floors and spider webs in hard-to-reach places, made her jittery. She always expected to see evil eyes leering from the darkness.

Most bothersome, however, was that the apartment smelled like a musty cellar. It took Estelle days to wash the stench out of her clothes and hair. But she never could get it out of her mind. “The place smells like a mausoleum that's been sealed for centuries,” she’d complain to Eva.

With an exaggerated shiver, Eva once replied, “it’s as if the walls are crawling with invisible cockroaches. I always expect to feel them creeping up my legs.”

Visiting Mrs. O’Brien made Estelle wonder about the existence of good and evil. Her husband would dismiss her concerns. “Religion hasn’t been proven to me. I believe that all good and evil exists right here on earth.”

Like many women in her day, Estelle accepted her husband's opinions as her own. Men know best about things like religion.

Despite their doubts, she and Jacob joined the local "Brighton Heights Church,” where they had their children baptized and later planned to send them to Sunday school." It's nice for little children to believe in God,” the couple agreed.

Kissing Naomi’s soft skin while the other children played nearby, Estelle whispered, “You have an important destiny, Precious One. You were born with the veil.”

But neither the veil nor destiny would prevent Naomi from growing into a challenging toddler. Her angelic freckled face, framed with curly, chestnut hair belied her strong-willed personality. Throwing temper tantrums, she'd forcibly spit out food she didn’t like. Nor could she be restrained by any boundaries, such as her crib. Climbing from its confines, she would crawl into forbidden places.

Wiping her brow after an exhausting day with Naomi, Estelle often moaned to Jacob, “That girl needs to be watched constantly.”

One spring afternoon, following Naomi’s first birthday, Estelle opened some windows to let the balmy air inside. She then leaned her big, buxom body out the kitchen window to reel some freshly washed sheets out onto the clothesline. Estelle moved quickly so she could sit and chat with her sister Wilhelmina, who had come to visit. The sisters were especially close after a childhood bout with black diphtheria nearly claimed Wilhelmina. It was said she contracted the illness after falling into an open sewer.

A chesty blonde, Wilhelmina (whom everyone called Willie) was nearly her sister’s twin. “Zaftig” (Yiddish for plump) is what family members called them. Waiting for her sister, Willie sat on the sofa puffing on a cigarette. As always, the two called back and forth to each other in English and German.

“I’ll be there as soon as I get these clothes hung and the children down for a nap,” Estelle shouted.

Scooping up Naomi who’d been playing on the floor, she disappeared into the children’s bedroom. Wiping her hands on her apron, she later emerged triumphant.

“I can’t believe I got them all to sleep at the same time!" she said, plopping down next to Willie.

In the lazy afternoon, a warm breeze blowing through the windows made the curtains flutter. With their fleshy calves sticking out of their skirts and their plump arms from their sleeves, the sisters talked and laughed.

Puffing defiantly on a cigarette, Willie blew smoke rings.

Estelle raised her eyebrows. “It’s not ladylike to smoke. You should take up something more feminine like embroidery,” she added, motioning toward an embroidery hoop on which she had been stitching intricate flowers.

Willie tossed her short crop of golden curls and rolled her blue eyes. “Mutter (Mother) taught me how to embroider, just like she did you. And I wish you wouldn’t talk to me like I'm an evil child. Our ‘dear’ stepfather, Johann does, and I'm tired of hearing what good girls should and shouldn’t do.”

Casting Willie her indignant, big sister look, Estelle gave a small lecture. “It’s almost scandalous that you've been living alone since you took that job at the candy factory in Brooklyn.”

Willie took a long puff on her cigarette. “As you well know, I had no choice. Stepfather told me to leave home after I had my hair bobbed. Brother Franz already left because he couldn't stand the strict rules.”

“Stepfather thumps his Bible too much and takes his born-again religion too far,” Estelle groaned.

Willie nodded while squashing her cigarette in an overloaded ashtray. “After all these years, I’m still sad that Vater (Father) died. Stepfather has ruined Mother’s life with his silly rules. And why did Mother ever have his baby? Little Karl’s cute, but Mother’s almost fifty and has sugar diabetes.”

Estelle frowned. “If all religion offers is rules and endless babies for women, how can you still believe in God?” “A girl at my job told me that religion isn’t the same as knowing God,” Willie answered. “And she says ‘God is Love’”1

“Maybe God is only a figment of our imagination," Estelle injected, rising from the couch to peek in on the children. A few moments later, her screams filled the tiny apartment. Leaping to her feet, Willie ran over.

“What happened?” she gasped, bursting into the children's bedroom.

“Naomi’s gone!” Estelle screeched. “I can’t find her anywhere.”

Awakened by the turmoil, Estelle’s two other children stood in their cribs crying: Three-year-old Jacob with his mother's golden curls and two-year-old Ruth, rubbing her chocolate-brown eyes.

Panic escalated as Willie rushed around the room searching for little Naomi. Willie looked in the closet, under the cribs, behind a chair. Suddenly, her gaze riveted on an open window and she yelled, pointing. “She must have crawled out onto the fire escape!”

Instantly, both women thundered to the window, their heavy legs pounding the wooden floor. Willie thrust her big body outside, but no baby could be seen on the fire escape. Willie's heart pounded as she looked down, then called to her sister, “thank God she didn’t fall to the ground!”

Almost wincing, she looked up. Straining to see beyond the white sheets flapping on clotheslines, her eyes scanned the fire escapes ascending to the second, third and fourth floors. Then, glancing toward the roof, she saw Naomi's gleaming, auburn hair. The baby’s smiling face looked down at her. “Himmel! (Heavens!) She’s on the roof!” Willie shouted. “I’m going up to get her.”

After hoisting her plump legs onto the windowsill, Willie squeezed her body out the window and onto the fire escape. She got there in time to see Eva running hysterically across the street, screaming, “Naomi’s on the roof! Naomi's on the roof!”

“I know,” Willie called out. “I’m on my way.”

Realizing her dress was blowing up in the wind, Willie tried to hold it down while scrambling up the iron ladder. In a sweet but shaky voice, she called to the baby. “Auntie Willie's coming, Liebchen. (Sweetheart) Don’t move. Wait for me.”

By this time, the neighborhood lech, old Mr. Brown was leering out a nearby window at the spectacle of slip and legs. Even in the turmoil of the moment, Willie managed to cast him an indignant look. “Schweinhund!” (Swine!) she yelled.

At last, reaching Naomi, Willie extended her arms. Squealing with delight, Naomi tumbled into them. From the window, Estelle cried; from the ground Eva jumped up and down applauding, and from his window, old Mr. Brown continued to leer.

Naomi turned her smiling face into the wind and sun. Only one other knew how much she had enjoyed herself. Though no one but the baby had seen him, his powerful arms had kept her safe.

Such thrills were rare for Naomi. As a toddler, she caught one illness after another: pneumonia, tuberculosis and scarlet fever. Her face as pallid as a sheet, she’d watch old, hunchbacked Dr. Johnson bending over her and pacing anxiously back and forth.

Standing in the doorway, her father would look grimfaced and her mother, teary-eyed. With hard economic times beginning to settle over the land, the couple sometimes paid the doctor with a meal. When they were able, they would give him a few coins. Other neighbors, who raised chickens, often sent him home with one clucking under his arm.

Time after time, Naomi would look out her window to see the old doctor pulling up with his horse and buggy. If he wasn’t coming to care for her, he was coming to care for Ruth or Brother Jacob, who caught the same illnesses. Their crying and coughing frightened Naomi.

One Palm Sunday morning when Naomi was three-years-old, an eerie stillness settled over the apartment. Someone whispered that Brother Jacob had died. Later that day, choked sobs whispered the same about Ruth.

Without her brother and sister, little Naomi felt lonely in the weeks that followed. She also felt afraid and confused. Die must mean something bad. Grownups cry when they say it.

On a rainy afternoon, the girl found her mother weeping while scrubbing laundry in the washtub. Streaming down her face, Estelle’s tears dripped into the soapy water. Naomi tugged on her mother’s housedress.

“Mommy,” she questioned, looking up. “How come Jacob and Ruth aren’t here anymore? Where did they go?”

Estelle hesitated a moment then said the only thing she could. “Your brother and sister went to heaven, Darling.”

Heaven? the child wondered. Where’s heaven?

Even though Naomi’s siblings had gone to that mysterious place, Jacob and Estelle made sure the child didn't forget them. Their memory was kept alive through conversations within the family.

Shortly after the children’s passing, Naomi’s father began to smell more like what her mother called whiskey. Naomi knew it had something to do with him hiding glass bottles around the apartment and in the cellar. He also began spending more time at a restaurant where Aunt Willie had whispered that bootleg whiskey was served. Naomi’s father and Uncle Franz sometimes took the little girl there with them. While nibbling on a sandwich, Naomi would watch the men gulp down one shot-glass of whiskey after another.

Even though Naomi felt lonely without her brother and sister, a kind man would appear to her. Sometimes she'd be playing in her room and suddenly, he would be there, watching over her with tender, caring eyes. Naomi knew she could trust him because he had a fatherly presence. Although no one had told her, she also knew his name was Jesus.

Taking her small hand in his, he’d smile and say, “You're a good little girl. I love you.”

And whatever love was, Naomi knew it felt like a ray of warm sunshine and a kiss. In other words, it felt like Jesus.

Naomi never could remember who she talked to about him, but they smiled the way grownups smile at childish things. They also told her that Jesus wasn’t real. This confused the little girl. Naomi believed that Santa Claus was real.

Why wouldn’t Jesus be real too? But if a big person said he wasn’t, it must be true.

After that, Naomi didn’t see her kind friend anymore. Although she never forgot his visits, they began to seem like a dream. Gradually, Naomi came to believe that’s what they had been all along—a dream or her imagination. She told her friend Jenny about them, but made her promise to tell no one.

Jenny’s brown eyes lit-up as she moved tangled hair from her dirt-smudged face and told secrets of her own.

“I like to pretend I’m a boy, and sometimes I dress like one too. I do that cause when I’m big, I’m gonna run away from my mean uncle an’ ride the rails with the hobos.”

Naomi’s mother mildly protested the girls’ friendship. "You know we love Jenny and feel bad that after her parents died, she went to live with that drunken uncle. Everyone knows he beats her, but she should be playing with dolls, not boys and baseballs. So should you. The neighbors call Jenny a wildcat. If you keep playing with her, they’ll call you one too.”

“I don’t care!” Naomi protested, her small face determined.

And Naomi truly didn’t care. She would have worn the title “wildcat” like a badge of honor.

No disciplinarian, Estelle relented and welcomed the ragamuffin into her home.

After Naomi turned four, a worrisome cloud descended over the land. Grownups began using strange words like "stock market collapse” and “depression.”

When Aunt Eva’s husband lost his job, she ran to Estelle and through blackened eyes, wept in her arms. “Ray beat me again! I don’t know why he had to do that!”

Estelle smoothed her sister-in-law’s luxurious, ink-colored hair. “I’m sorry for you, Eva. I understand. We women have it so hard. Men mistreat us and there’s nothing we can do.”

When Jacob came home from work one afternoon, it was Estelle's turn to cry.

“I lost my job today,” he said, looking stunned.

Collapsing onto a chair, Estelle buried her face in her hands. “Oh Jake, Jake,” she wept. “How will we pay our bills? How will we feed little Naomi?”

Before long, Aunt Willie moved in with the family, sleeping in a tiny room near Naomi’s. Choking back tears, Estelle thanked her sister for giving them the money she'd been putting away for the wedding she hoped to have one day. With a bittersweet laugh, Aunt Willie joked about staying a virgin forever—whatever that was, Naomi didn't know.

Even with Aunt Willie’s help, the family still stuffed cardboard into their worn shoes and lined their coats with newspaper. The adults also told Naomi that they liked eating onion sandwiches. Years later she would learn they really didn't, and had saved the better food for her.

Usually happy and well fed; the child never knew that her parents and aunt often went to bed hungry. And, when Uncle Franz began eating meals there too, the adults went to bed hungrier still.

Blissfully unaware of the suffering, the little girl enjoyed having her aunt and uncle close by. Uncle Franz gave her horsy rides on his back. He would also sit her on his knee to tell stories about three talking horses. Naomi didn’t realize the yarns about Blackie, Goldie and Brownie, first came into focus through the bottom of her uncle’s beer mug.

Although Uncle Franz came and went, Naomi was glad Aunt Willie stayed, even when her father landed a projectionist's job at the new, Saint George Theater. In English and German, a medley of sweet songs flowed from Aunt Willie’s lips. And when snuggling with Naomi on a chair, she could recite stories and nursery rhymes for hours on end.

On scary nights when Naomi remembered stories about Uncle Stanley’s friend being found dead in an alley, she'd crawl into Aunt Willie’s bed. Curled-up against her soft skin, little Naomi savored the fragrance of talcum powder. And when Willie could sneak a cigarette beyond Jacob's disapproving glance, Naomi smelled tobacco too. To the little girl, these scents represented home and security.

All the neighborhood children loved Aunt Willie. The candy she brought them from the factory was a treat during hard times. But her dimpled smiles and enveloping hugs were sweeter than any candy. Even Jenny the wildcat couldn't resist being gathered inside Aunt Willie’s fleshy arms and being called, Liebchen.

Willie and Estelle were also liked by the gaunt and unshaven men who came to the door begging for food. The sisters gave the men whatever they could spare. If food was sparse, it might be one of the onion sandwiches. When food was more plentiful, the men would be invited for a “sit down” dinner with the family.

One afternoon Naomi found a large, charcoal-scratched “X” on the sidewalk, outside her apartment building.

“What does that mean?” the child asked.

Aunt Willie explained. “When a family feeds a hobo, he'll often mark the sidewalk in front of the home. It’s a sign to other hobos that the people inside will share what they can.”

One hobo stood out from the rest. Winding through the neighborhood and courtyards, he’d play mournful melodies on a violin. From a distance, Naomi would hear selections that she later recognized as classics, such as Meditation, The Swan and most often, the haunting Träumerei. (Dreaming)

After she called for her mother and aunt, they’d lift her to the window. Together, the women and child would listen to the music drifting closer. When the unshaven maestro paused in the courtyard below, Estelle and Willie would toss him coins wrapped in paper. Pulling a whiskey bottle from his coat, he would guzzle greedily, then stagger across the street to serenade Eva. She also tossed him coins. Like the other hobos, the old violinist sometimes joined the Kahn family for a “sit down” meal.

Naomi once overheard her mother and Aunt talking about him. “Before the depression he was a concert violinist, playing at places like Carnegie Hall. Then he lost everything and began to drink. Now look at him. He still plays beautifully, but isn’t it a shame?”

Indeed it was. As he played, the howling wind, groaning foghorns and mournful violin joined in a lament, echoing the pain and suffering, rampant during those troubled times.

Copyright © Flora Reigada. All rights reserved.

This book is available from major book dealers.

Click on the logos below for more details:

The complete book is also available in

Adobe

PDF (.pdf) format for only $4.95.

Pay through Paypal.

Pay through Paypal.